Warren Buffett’s annual letter to shareholders for the 2012 year was released on 1 March 2013. The letter, as usual, contained Buffett’s thoughts on a number of topics as well as informing shareholders of how their company went in the past year.

Contents

Berkshire Hathaway Financial Year 2012

Buffett announced that the book value of the company had increased by 14.4 per cent per share for the year, compared to 4.6 per cent in the previous year. This was not a startling rise, compared to the overall market. Buffett was disappointed in the result, noting that the company had underperformed in recent years but felt that a continuation of the company’s investment principles would ensure that Berkshire outperformed the market over the long term.

To date, we’ve never had a five-year period of underperformance, having managed 43 times to surpass the S&P over such a stretch. (The record is on page 103.) But the S&P has now had gains in each of the last four years, outpacing us over that period. If the market continues to advance in 2013, our streak of five year wins will end.

One thing of which you can be certain: Whatever Berkshire’s results, my partner Charlie Munger, the company’s Vice Chairman, and I will not change yardsticks. It’s our job to increase intrinsic business value – for which we use book value as a significantly understated proxy – at a faster rate than the market gains of the S&P. If we do so, Berkshire’s share price, though unpredictable from year to year, will itself outpace the S&P over time. If we fail, however, our management will bring no value to our investors, who themselves can earn S&P returns by buying a low-cost index fund.

Charlie and I believe the gain in Berkshire’s intrinsic value will over time likely surpass the S&P returns by a small margin. We’re confident of that because we have some outstanding businesses, a cadre of terrific operating mangers and a shareholder-oriented culture. Our relative performance, however, is almost certain to be better when the market is down or flat. In years when the market is particularly strong, expect us to fall short.

He emphasised that the businesses owned by the company had done well but there had been no major purchase during the year. However, 2013 has started big with the buy out of Heinz.

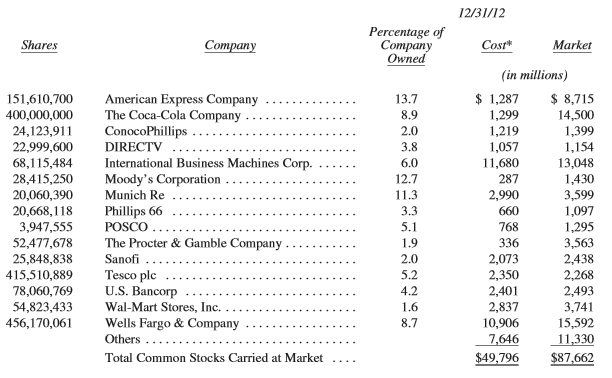

Berkshire Hathaway holdings in publicly listed companies

Berkshire Hathaway holds shares valued at $1 billion or more in the following companies.

Comment

There have been significant increases in the holdings of shares in Tesco and Walmart (up) and Proctor and Gamble (down) during the year and Johnson and Johnson have disappeared from the major list entirely. The big new stock is DIRECTV, chosen not by Buffett but his investment team. DIRECTV is a direct broadcast satellite service provider with nearly 20 million customers.

The insurance business

According the Buffett, they ‘shot the lights out’, and ‘neither rain nor storm nor gloom at night can stop … the little lizard’ (GEICO). He acknowledged that part of Berkshire’s investment success came through its access to the funds available from the premiums paid to its insurance companies which are low cost, but only low cost if the insurance companies do not make substantial underwriting losses. He asserted that the Berkshire companies were in a good position as to their underwriting business, a factor which he attributed to the skills of the insurance business managers. He cautioned that not all insurance companies were in this position.

Fortunately, that’s not the case at Berkshire. Charlie and I believe the true economic value of our insurance goodwill – what we would happily pay to purchase an insurance operation producing float of similar quality – to be far in excess of its historic carrying value. The value of our float is one reason – a huge reason – why we believe Berkshire’s intrinsic business value substantially exceeds its book value.

Let me emphasize once again that cost-free float is not an outcome to be expected for the P/C industry as a whole: There is very little “Berkshire-quality” float existing in the insurance world. In 37 of the 45 years ending in 2011, the industry’s premiums have been inadequate to cover claims plus expenses. Consequently, the industry’s overall return on tangible equity has for many decades fallen far short of the average return realized by American industry, a sorry performance almost certain to continue.

Underwriting losses were only one factor in what Buffett sees as poor times ahead for insurance companies. Irrational competition by insurance companies for customers and the possibility of increasing national disasters make it essential to have good risk management.

The American economy

Buffett reaffirmed his faith in the American economy and suggested that it was not a good thing to be out of the market at the moment.

American business will do fine over time. And stocks will do well just as certainly, since their fate is tied to business performance. Periodic setbacks will occur, yes, but investors and managers are in a game that is heavily stacked in their favor. (The Dow Jones Industrials advanced from 66 to 11,497 in the 20th Century, a staggering 17,320% increase that materialized despite four costly wars, a Great Depression and many recessions. And don’t forget that shareholders received substantial dividends throughout the century as well.)

Since the basic game is so favorable, Charlie and I believe it’s a terrible mistake to try to dance in and out of it based upon the turn of tarot cards, the predictions of “experts,” or the ebb and flow of business activity. The risks of being out of the game are huge compared to the risks of being in it.

Newspapers

Buffett explained why he is buying into regional newspapers at a time when doom and gloom surround the print media. He explained that, in the days before television, newspapers abounded and even the smaller cities had more than one newspaper with local news, broader-based news, and advertising. As television became the go-to-place for news, cities other than the really big ones became one newspaper towns and were lucrative because they did things that television networks did not do or did not do well; they covered local news and local advertising. Buffett recited an anecdote about a newspaper publisher who attributed his wealth and prominence to two things - nepotosm and monopoly.

The world has changed dramatically with the Internet and a lot of the information that used to be contained in newpapers - news, stock prices, sport, even the literally mocked shipping news - is available at the touch of a key, is current, and is mostly free. What the Internet does not do well is local news and this creates a place for local newspapers.

Newspapers continue to reign supreme, however, in the delivery of local news. If you want to know what’s going on in your town – whether the news is about the mayor or taxes or high school football – there is no substitute for a local newspaper that is doing its job. A reader’s eyes may glaze over after they take in a couple of paragraphs about Canadian tariffs or political developments in Pakistan; a story about the reader himself or his neighbors will be read to the end. Wherever there is a pervasive sense of xommunity, a paper that serves the special informational needs of that community will remain indispensable to a significant portion of its residents.

Buying good regional newspapers will be a continuing strategy for Berkshire Hathaway and we welcome this.

Charlie and I believe that papers delivering comprehensive and reliable information to tightly-bound communities and having a sensible Internet strategy will remain viable for a long time. We do not believe that success will come from cutting either the news content or frequency of publication. Indeed, skimpy news coverage will almost certainly lead to skimpy readership. And the less-than-daily publication that is now being tried in some large towns or cities – while it may improve profits in the short term – seems certain to diminish the papers’ relevance over time. Our goal is to keep our papers loaded with content of interest to our readers and to be paid appropriately by those who find us useful, whether the product they view is in their hands or on the Internet.

Comment

We have studied Buffett for a few years now and while it is certain that his financial skills and boldness have contributed greatly to his success, we believe that it is his ability to think differently to others that has made him the greatest investor of them all. This is an example of his different way of thinking.

Capital intensive businesses

Berkshire’s two main capital intensive businesses are BNSF Railway and MidAmerican Energy.

Now we know that Buffett does not like to buy shares in companies that require continuing large inputs of capital, where the capex exceeds depreciation and replacement. This is one reason why he has generally steered clear of the large airline companies (plus they are in a very competitive industry).

Where however, Buffett has control of the business and where the market is regulated, Buffett is not averse to capital intensive investments. BNSF, for example, carries about 15 per cent of all inter-city freight and has good contracts in a regulated industry. MidAmerican operates across 10 American states and is a, if not, the leader in renewable energy, a good position to be in having regard to the new focus on the environment by the Obama administration promoted by the President in his 2013 State of the Union report.

The good news is, we can make meaningful progress on this issue while driving strong economic growth. I urge this Congress to pursue a bipartisan, market-based solution to climate change, like the one John McCain and Joe Lieberman worked on together a few years ago. But if Congress won’t act soon to protect future generations, I will. I will direct my Cabinet to come up with executive actions we can take, now and in the future, to reduce pollution, prepare our communities for the consequences of climate change, and speed the transition to more sustainable sources of energy.

Four years ago, other countries dominated the clean energy market and the jobs that came with it. We’ve begun to change that. Last year, wind energy added nearly half of all new power capacity in America. So let’s generate even more. Solar energy gets cheaper by the year – so let’s drive costs down even further. As long as countries like China keep going all-in on clean energy, so must we.

In the meantime, the natural gas boom has led to cleaner power and greater energy independence. That’s why my Administration will keep cutting red tape and speeding up new oil and gas permits. But I also want to work with this Congress to encourage the research and technology that helps natural gas burn even cleaner and protects our air and water.

Buffett has acknowledged that these two companies are going to require large capital contributions in the future but believes that the investment will return reasonable earnings in their respective regulated industries. The figures would seem to justify this belief with both companies returning increased profits over 2011. And he is confident that the earnings of both companies can more than adequately cover present and potential debt.

A key characteristic of both companies is their huge investment in very long-lived, regulated assets, with these partially funded by large amounts of long-term debt that is not guaranteed by Berkshire. Our credit is in fact not needed because each business has earning power that even under terrible conditions amply covers its interest requirements. In last year’s tepid economy, for example, BNSF’s interest coverage was 9.6x. (Our definition of coverage is pre-tax earnings/interest, not EBITDA/interest, a commonly-used measure we view as deeply flawed.) At MidAmerican, meanwhile, two key factors ensure its ability to service debt under all circumstances: the company’s recession-resistant earnings, which result from our exclusively offering an essential service, and its great diversity of earnings streams, which shield it from being seriously harmed by any single regulatory body.

Whether companies should pay dividends

Most companies pay dividends and this keeps shareholders happy as it gives them a return for the capital locked up in a shareholding. Berkshire Hathaway has never paid a dividend under Buffett’s control and this has caused some dissatisfaction among shareholders as the only way that they can get walking-around money is to sell some of their stock. It has also dissuaded some investors and institutions from buying Berkshire stock because they need to generate income from their investment.

Buffett does not advocate that companies should not pay dividends. His view is that if a company can use its earnings productively to grow the company (investing in income producing assets, in improving productivity, and buying back shares when the price is below its intrinsic value), it should do so, rather than return the money to shareholders by way of dividends. If, and only if, the managers of the company cannot do this, they should return the money to its owners by way of dividends.

Buffett believes that he and Charlie Munger can and do do this and this is why Berkshire does not pay dividends and is unlikely to do so under the present regime. So what about those shareholders who need income? Buffett’s solution is for them to sell a certain portion of their shareholdings as he does (well, actually he gives his to charity) and they will be better off financially than if the company paid dividends. How is this possible? Buffett explains it like this (Caution: you need to think this one through.).

We’ll start by assuming that you and I are the equal owners of a business with $2 million of net worth. The business earns 12% on tangible net worth – $240,000 – and can reasonably expect to earn the same 12% on reinvested earnings. Furthermore, there are outsiders who always wish to buy into our business at 125% of net worth. Therefore, the value of what we each own is now $1.25 million.

You would like to have the two of us shareholders receive one-third of our company’s annual earnings and have two-thirds be reinvested. That plan, you feel, will nicely balance your needs for both current income and capital growth. So you suggest that we pay out $80,000 of current earnings and retain $160,000 to increase the future earnings of the business. In the first year, your dividend would be $40,000, and as earnings grew and the one third payout was maintained, so too would your dividend. In total, dividends and stock value would increase 8% each year (12% earned on net worth less 4% of net worth paid out).

After ten years our company would have a net worth of $4,317,850 (the original $2 million compounded at 8%) and your dividend in the upcoming year would be $86,357. Each of us would have shares worth $2,698,656 (125% of our half of the company’s net worth). And we would live happily ever after – with dividends and the value of our stock continuing to grow at 8% annually.

There is an alternative approach, however, that would leave us even happier. Under this scenario, we would leave all earnings in the company and each sell 3.2% of our shares annually. Since the shares would be sold at 125% of book value, this approach would produce the same $40,000 of cash initially, a sum that would grow annually. Call this option the “sell-off” approach.

Under this “sell-off” scenario, the net worth of our company increases to $6,211,696 after ten years ($2 million compounded at 12%). Because we would be selling shares each year, our percentage ownership would have declined, and, after ten years, we would each own 36.12% of the business. Even so, your share of the net worth of the company at that time would be $2,243,540. And, remember, every dollar of net worth attributable to each of us can be sold for $1.25. Therefore, the market value of your remaining shares would be $2,804,425, about 4% greater than the value of your shares if we had followed the dividend approach.

Moreover, your annual cash receipts from the sell-off policy would now be running 4% more than you would have received under the dividend scenario. Voila! – you would have both more cash to spend annually and more capital value.

This calculation, of course, assumes that our hypothetical company can earn an average of 12% annually on net worth and that its shareholders can sell their shares for an average of 125% of book value. To that point, the S&P 500 earns considerably more than 12% on net worth and sells at a price far above 125% of that net worth. Both assumptions also seem reasonable for Berkshire, though certainly not assured.

Moreover, on the plus side, there also is a possibility that the assumptions will be exceeded. If they are, the argument for the sell-off policy becomes even stronger. Over Berkshire’s history – admittedly one that won’t come close to being repeated – the sell-off policy would have produced results for shareholders dramatically superior to the dividend policy.

In Buffett’s case it has worked like this. He says that the book value of his current interest in Berkshire in 2005 was $28.2 billion and it is now worth $40.2 billion. Even though in that time he has given away a heap of shares (shareholding reduced from 712,497,000 B-equivalent shares - split adjusted - to 528,525,623), the value of his holding has grown by $12 billion, a rise of 43 per cent. And the other advantage is that in most regimes the tax payable on capital gains is less than that payable on income.

Comment

This is another example of Buffett’s original thinking. I think I will write to the directors of companies in which I hold shares and where management is putting earnings to good use and ask them to stop paying dividends.

The succession

Buffett fulsomely praised Todd Coombs and Ted Weschler, two possible successors, and increased the amount of Berkshire money that they have to play with. He said that they are both young and will be managing the Berkshire portfolio after he and Munger have gone. As he has done in the past few letters, he has again acknowledged the contribution made to the underwriting business of Ajit Jain but in no greater terms than he praised other Berkshire insurance managers.

Nothing in Buffett’s comments have caused us to alter our belief that the leadership of the company will, after Buffett leaves, be divided.

Books

As in past years, Warren took the opportunity to recommend some good books for investors. We have added these to our list of Buffett’s book recommendations.